Dir:- Marcus Nispel

Starr:- Jessica Biel, Eric Balfour, R. Lee Ermey, Jonathan Tucker, Erica Leerhsen, Mike Vogel

Scr:– Scott Kosar

DOP:- Daniel C. Pearl

Producer(s):- Michael Bay, Mike Fleiss

Any self-respecting horror aficionado would have to admit that the last two decades have not been kind to their beloved muse. Aside from the ongoing self-cannibalisation of the genre through the myriad risible remakes of classic seventies and eighties schlock masterworks, there has been an increasing reliance on the cheap shocks of ‘horror’ over the sustained psychological trauma of ‘terror’. Even vaguely original entries into the genre, such as Cabin Fever, Hostel and Ils have ruined much of their impressive set-ups with a sudden tilt into Nine Inch Nails-inspired pop video territory, or an unwillingness to take their premise as seriously as the truly terrifying demands. Perhaps the most reprehensible influence on the modern horror film has been the rockstar turned filmmaker Rob Zombie, whose woeful movies include the frankly embarrassing House of 1000 Corpses, the marginally more bearable follow-up The Devil’s Rejects and the truly inept remake of one of the great horror movies Halloween. Zombie’s aesthetic is predicated on little more than trawling through the broadest of clichés from what could loosely be described as ‘Southern Gothic’, ramping up the bloodletting and carnage to operatic and artless levels that terrify in much the same manner as extended exposure to MTV2, or A & E’s serial-killer biography series. It’s grotesque without being scary, torturous in a puerile and juvenile manner, defined by an overarching sense of voyeuristic glee and wanton fetishistic sub-cultural fascination. Put bluntly he’s no Dario Argento, even if he thinks he is.

Zombie has been joined in the past decade by a cavalcade of bored horror-geeks who lack the élan, technical sophistication, blackly comic sensibilities and generally inventive mindset of an Eli Roth or Adam Mason. Thus the horror genre has plodded, near comatose, through remakes of everything from The Last House on the Left to Friday the 13th (a franchise that had already drained itself dry through spin-offs and sequels that were in the double digits), whilst producing farcically bovine and formulaic new franchise fodder such as the Final Destination movies. Whatever vital spark had reignited horror in the late sixties and early seventies, has long since been extinguished and following the genre with any expectation of even the slightest cinematic innovation, is akin to some of the more egregious forms of masochism.

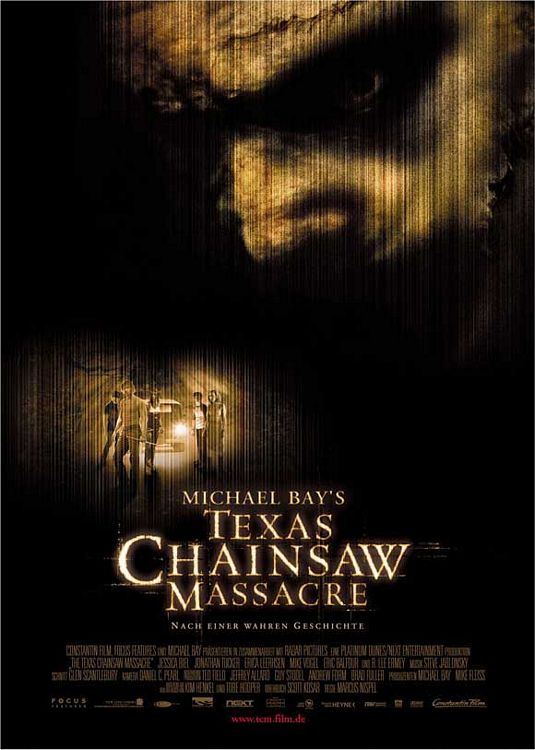

Line-up here in order of whose going to get dispatched first. Now remember one of you has to scream a lot and at least one of you will be suspended from a meathook in a pointless Christ pose.

All of this is merely setting a context within which one can even vaguely begin to critically dissect the sorriest, and most unnecessary, remake of the past ten years. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was perhaps the most beloved and ghoulish of the seventies explosion in grindcore and splatterhouse horror films. It was directed by one of modern horror’s most talented filmmakers, Tobe Hooper (even if his career hasn’t quite met the heights one might have projected for it), and deservedly ranks as a great example of a movie that manages to balance sheer, visceral horror, an undeniable sense of the grotesque, the darkest of satires and excruciating terror. Not only was this 1974 horror masterpiece an intimidating watch, it also managed to be highly innovative, with Hooper and his cast and crew pushing themselves to the very limits of crazed cinematic ingenuity. Even after nearly four decades The Texas Chainsaw Massacre endures as a profoundly unsettling work, with perhaps one of the best opening sequences in horror cinema and sound design that still seems startlingly contemporary.

The most terrifying aspect of this stultifyingly dull ‘reimagining’ can be experienced without watching a single second of the film. A simple perusal of the credits on the back of the DVD will alert the keen-eyed cinephile to the presence of that most odious of Hollywooden individuals, here listed as producer. Yes, the name Michael Bay is as petrifying as any masked, blade-wielding maniac, from Michael Myers to Ghostface. Bay’s trademarked brainless bombast has been applied to such utterly charmless cinematic offerings as Bad Boys, Armageddon and Pearl Harbour. You’re average impressionable and rebellious teen should find Bay’s work like Kryptonite to them, however as a true reflection of how ‘uncool’ modern youth has become, Bay’s works – particularly The Transformers movies – are lionised as if they were the equivalents of modern-day Alfred Hitchcock’s. The way that Bay has, in recent years, gone about systematically pissing all over some of the best horror movies of recent times (The Hitcher, Nightmare on Elm Street, Amityville) is an act of desecration roughly equivalent to the manner in which Universal have disinterred their classics of the thirties and forties into a series of cumbersome big-budget CGI-workouts for the tech nerds on their payroll. Bay is so patently anti-film that it beggars belief that he continues to be indulged by both studio executives, horror luminaries and a significant proportions of the paying public. It surely isn’t snobbish elitism to suggest that such a situation could only continue to be tenable due to the absolute paucity of horror product.

So to the film itself. The original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was a mordantly funny take on American family values post-Summer of Love, with a lo-fi visual style and texture that was primarily the result of a lack of adequate budget, but also showcased Hooper’s keen awareness of the power of claustrophobia, as well as the truly grueling spectacle. In the remake, German pop-video director Marcus Nispel – who reunited with Bay to helm the latest version of Friday the 13th – works from a script by the writer of The Machinist, Scott Kosar. This script opts to frame events as if they were occurring in some bizarre and nonsensical Cold Case dramatisation, replete with a bogus disclaimer at the movie’s close, much like the far more effective Liv Tyler vehicle The Strangers. It also reduces much of Hooper and Kim Henkel’s hysterical humour to the kind of frat-boy, snigger-inducing chauvinism that serves as sophisticated mainstream comedy nowadays. Whereas Edwin Neal’s Hitchhiker figure in the original was a disturbing blend of wild physical comedy and almost psychopathically unhinged intensity, in this remake Nispel and Kosar transform the Hitchhiker into a young female victim, who quickly dispatches herself with a gun whilst in the back of the van. The group of twentysomethings in the remake are more materialistic, narcissistic and generally Californian-perfect than in the original film, which proves particularly problematic when Nispel and Kosar attempt to shoehorn in a whole load of spuriously contrived moral dilemmas.

Hooper’s lean original film reduced everything to the essentials of atmosphere and terror. The rudiments of character were skimmed over, so the audience were aware that Franklin was a whiny and manipulative cripple and Sally was a tenacious survivor, but there was very little unnecessary psychological probing going on. What counted in the 1974 version was that the audience believed the horrific nature of these encounters with a flesh-masked monster run amok. The set-up of the original film is thus mercifully brief, with the suddenness of the violence literally hitting home like a sledgehammer. Despite the film’s fearsome reputation it is actually a surprisingly restrained work, that manages to conjure up a feverishly hallucinogenic final fifteen minutes, that mines similarly morbid material to Bob Balaban’s grossly overlooked Parents. The family that Hooper constructs is a dysfunctional patriarchy, with the only vaguely female presence being the confused and monstrous figure of Leatherface, who oscillates wildly between moments of animalistic rage and fury, and stereotyped submissive female domesticity. There is a sense that Hooper and Henkel are knowingly playing with the idea of unchecked masculinity as both a corrupting and disfiguring force within the microcosmic structure of the family. Leatherface remains, throughout the film, ensconced in his flesh-mask, a contradictorily hulking and enigmatic presence, rarely examined in detail by Hooper’s remote camera, but rather glimpsed from behind shutters and screens, or from obscure angles, or emerging from the chaos of a darkened forest. Instead it is the other, more colourful characters, that hog centre-stage, with the three generations of men gathered round the table toward the end of the movie in a deliberately grotesque exaggeration of Southern States stereotypes.

Contrast Hooper and Henkel’s relative subtleties with the garbled irrelevancies of Nispel and Kosar’s effort. Playing to the Rob Zombie crowd Nispel creates a whole hamlet of freakishly inbred Deep South caricatures, from the feral kid Jedidiah (David Dorfman), to the wheelchair-bound amputee old codger (Terrence Evans). Whereas the dysfunctional family of Hooper’s nightmare vision is a deformed patriarchy, Nispel appears to create a far less convincing family set-up in which Luda Mae (Marietta Marich) plays the lickspittle matriarch of Sheriff Hoyt’s (R. Lee Ermey) hellish brood. Ermey’s performance as the Sheriff is as lacking in nuance, as Jim Siedow’s original patriarch was slathered in it. Whereas the latter figure was a slippery customer, conveying a little down-home charm, along with a certain odiousness and barely restrained sadistic glee, Ermey’s usual figure of authority, is quite literally barking mad. Every time Ermey appears on screen, you can literally hear Laurence Olivier carving the ham in some heavenly anteroom for thespians.

Events in the first film seem to befall the group in rapid succession, barely giving them time to come to their senses and co-ordinate a means of getting away from their tormentors. In the remake they are given ample warning of what to expect and yet, like all imbecilic horror teens and twentysomethings since Friday the 13th onwards, continue to wander into danger, seemingly unwilling to except the evidence of their own senses. What makes this particularly unforgivable in this film is the ham-fisted way in which Kosar tries to imbue his group of young men and women with a series of pointless moral dilemmas, thus demonstrating that they have the capacity for some rational thought, before jettisoning it stage left, probably chased by a bear. There is no creeping terror or sudden horror to be had here, as everything is put out in broad daylight, with Leatherface becoming a serial-killer-cum-fetish object, replete with name, disfigured face and cheap pop-psychology profile as to his homicidal tendencies. Part of the lean and frenzied power of the first film was the manner in which it absolutely refused to explain the horrors at its core. Nispel, by using his daft framework for the film, attaches elements of the police procedural to the events that insinuate themselves into unwanted areas of the film, in effect demystifying and explaining, and thus further damaging the potential for the truly terrifying.

TEEN-BOY FANTASY: What is it with horror movie heroine's and there need to wear preposterous, boob-enhancing fashions?

Overall Nispel’s efforts feel much more staged than the original, which despite its meager budget managed to attain the verisimilitude of authentic nightmare. Hooper dwelt upon similarly fetishistic material in the original (the bones, the livestock, the rural American Gothic, the slaughterhouse paraphernalia), but there was a sense that the very worst remained outside of the field of vision – the circumscribed view of the camera lens. The real terror wasn’t what the audience saw of Leatherface and his family, but what lurked in the darkened corners of suggestion. Nispil’s aesthetic is predictably slanted toward visual literality and overkill. The Hoyt house here looks like a Trent Reznor inspired idea of the macabre, a setting that Marilyn Manson might consider a little too ‘camp’. The inanity of cutaway shots to peepholes, cattle, whirring windmills, dolls heads and carcasses is pretty much exemplary of the lack of sophistication evidenced throughout the film. Nispil seems to be suggesting that these images are inherently scary and foreboding, but they are so well worn and clichéd that they are very far from either of those things. The final nail in the coffin is the absolutely dreadful dialogue (“I guess that’s what brains look like, huh… like lasagne”), which Nispil clearly is aware of, as the movie becomes effectively monosyllabic for much of the closing half hour. There is absolutely no crackle of wit in Kosar’s script, something that the somber The Machinist shares with this earlier work. What the audience is left with is a sleep-inducing retread through every horror movie trope from the last two decades, with absolutely nothing worth recommending other than Jessica Biel’s vaguely interesting turn in the nominal lead. They really don’t make them like they used to.

Pros

- There are words and images, unfortunately.

- Jessica Biel is no Marilyn Burns, but she at least manages to navigate her conversion into a murdering sociopath with a slight degree of dignity.

- It’s mercifully short, clocking in at 94 mins.

Cons

- A script so bad that it should feature as an example of how not to write a film script in every film-writing course.

- As with so much of modern horror it mistakes showing for shocking, grotesquerie for terror.

- Manages to offer up none of the original’s intricate satirical commentary, reducing the comic elements to the kind of knockabout humour that serves as comedic entertainment nowadays.

Rating:- 1/10

Hilarious scathing review!

Yeah. I love classic horror and hate what horror has become. Does it show?