Dir:- Eugene Jarecki

DOP:- Étienne Sauret

Producer(s):- Kathleen Fournier, Eugene Jarecki

The brothers Jarecki (Andrew and Eugene) are two of the most fascinating documentary filmmakers working in America today. Andrew managed to direct perhaps one of the most brutal portraits of family conflict and division, in the deeply disturbing 2003 film Capturing the Friedmans. Whereas Andrew has since moved on to create feature films, Eugene has doggedly stuck to the task of examining modern American society and the projection of American interests abroad. His excellent analysis of the formation of the American military-industrial complex in 2005’s Why We Fight, lays some of the groundwork for his take on the most beloved, eulogised and divisive American president since FDR.

This is very much a conventional talking heads biographical documentary. In saying that, Jarecki’s analytical skills are scalpel sharp, so the figures that he has assembled to discuss Ronald Reagan’s life and legacy cut across the conservative-liberal political divide, enabling the director to demystify some of the rather fervid mythologies that have sprung up around America’s 40th President. Of the people interviewed, we have family (his son Ron and adopted son Michael), biographers (Lou Cannon and Edmund Morris), staff members (Arthur Laffer, an economic advisor, and Peter Robinson, his speechwriter), critics (Mark Hertsgaard and Robert Parry), advocates (Grover Norquist and Martin Anderson), as well as figures like MIT economist Simon Johnson, journalist Frances Fitzgerald, ex-CIA agent Frank Snepp and members of Reagan’s inner-circle, such as Pat Buchanan. Such an array of perspectives on Reagan gives the film, initially at least, a nicely balanced feel, whilst also highlighting the central difficulty of approaching Reagan as a subject, namely the manner in which Reagan appeared to keep his inner-life at a complete remove from almost everybody who knew him.

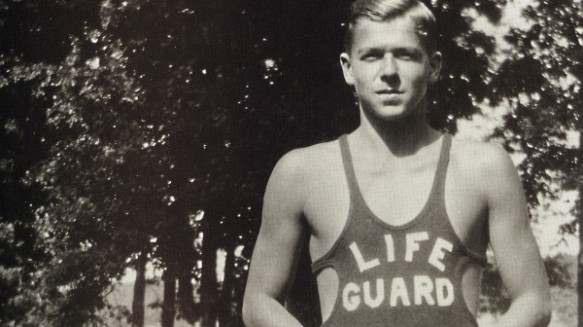

The film takes a linear approach to the narrative of Reagan’s life, going from his early days growing up in Tampico, Illinois, through his early careers as a lifeguard and sportscaster, right the way to his two-term stint as President. Jarecki carefully assembles little details about Reagan’s early years that come to have much greater bearing on his later role as President of the United States. The idea of him having been a lifeguard is commonly picked up by Reaganites as an example of his innate humanity. His military service is curtailed to clerical duties as a result of his chronic near-sightedness, something that takes on metaphorical import when considering the blind eye Reagan appears to have turned to certain covert military policies during his presidency. A certain aimlessness that seems to overtake Reagan at the end of the forties, when his film career begins to plateau, is thoroughly shaken off by the impact of Nancy Reagan (nee Davis) in helping to channel his energies into new careers as a Union spokesperson and a thoroughly convincing salesman (in particular for General Electric). The strikes that beset the motion picture industry in the late-1940’s and early 1950’s are seen as the main impetus for converting Reagan politically from a ‘haemophiliac liberal’ to a tax-cut conservative (and militant anti-Communist). The films that he was involved in during the forties and fifties are strongly associated with early twentieth century models of propaganda, and it is rather striking how Reagan’s role-playing of the All-American Hero, first fighting fascism and then Communism, prefigures his own conversion from liberal-socialism to liberal-conservatism (if that isn’t too much of a tautology). Perhaps, most crucially, in this early period of his life, Reagan is shown to have a clear preference for conducting the dirty work of politics behind closed doors. Whilst refusing to name names during the McCarthy witch-hunts, he nonetheless engages in informant behaviour, covertly reporting on his peers, and those he represents at the Screen Actor’s Union, to the intelligence services. Later on, during the low point of his presidency – the Iran-Contra Affair – this propensity to do things off the book, or away from the prying public eye, reveals itself to be a fundamental part of his White House operation.

Reagan is frequently contrasted with the ineffectual Jimmy Carter, the man he demolished in the 1980 election. Whereas Carter appeared to preside over one of the worst periods in recent American history, when the US began to show the first signs of doubt and introspection regarding its mythic role and ‘destiny’ in global affairs, Reagan was all about reinvigoration and reinvention. Jarecki seems to be suggesting that Reagan’s capacity for self-reinvention underpinned his vision for a national revival, that through a great slice of good fortune (Iranian prisoner releases on the day of his inauguration, the assassination attempt he survived) and sheer bloody-minded optimism his presidency manages to rejuvenate American spirits. A frequent trope in the film is the way in which Reagan’s speeches, even those from his time as a spokesperson for General Electric, frequently make reference to the individual ‘I’ joined to the collective ‘we’, carefully cultivating a direct rapport between himself and the people he talked to, as if they were equals in some shared destiny. Reagan had a penchant for Thomas Paine’s line “we have it within our power to begin the world over again”. This seems in many ways to fuel the American conservative movement’s contradictory attitude toward history as being a repository of universal human values, whilst also being something that can, in effect, be erased and reformed ad infinitum.

Despite the fact that Reagan and Carter are strongly linked as clearly contrasted presidencies, when looking for affinities with former presidents you need only really jump back to Richard Nixon. Jarecki’s film is at its most effective in the manner in which it deploys understatement. Perhaps the most understated element of the whole film is the fact that America’s most detested president in recent memory and, possibly, America’s most beloved, seemed to share eerily similar approaches to the highest office. Nixon barely even makes an appearance in the film, but echoes of Nixon’s presidency can be heard throughout the torturous revelations of the Iran-Contra Affair. What is perhaps most pertinent is the fact that Nixon has gone down in history as a cold, paranoid, remote Machiavellian political animal, whilst Reagan is viewed either as a bumbling buffoon surrounded by a power-hungry coterie of political operators, or as a strong president who exuded integrity and espoused a uniquely American ideology of freedom and renewed optimism for the role of the ‘little man’ to shape society. Reagan’s gift appears to have been his ability to sell a hokey, or potentially unpalatable narrative to the American people, like no other president before him. Not even Iran-Contra, with its various impeachable sub-plots, could damage Reagan’s standing as a popular president.

When it came to projections of Reagan's innate humanity, the fact his first career was all about saving lives seems almost too good to be true.

Jarecki is clearly unenamoured with the whole hoopla that modern American conservatism has brought to narratives of Reagan. The film progresses toward an end point that is overtly critical of the manner in which Reagan has been reinterpreted, by various different Republican and Tea Party figureheads, as a whole litany of things he patently wasn’t. Yet even more perceptively Jarecki is aware that this industry of Reagan myth-making has been made possible by the unique qualities of the man himself. Reagan’s carefully crafted salesman veneer, perfectly obscured the precise import of his beliefs, policymaking and political thinking. It also helped to distract, enabling Reagan to focus attention away from the more awkward parts of his presidency (the fact that he didn’t shrink government being perhaps the most obvious of these). Edmund Morris nails Reagan most astutely when describing his experiences of trying to write a biography of the man:

The difficulty about figuring Reagan out was he was not introspective. Therefore, to try and interview this guy who was so incurious about himself was very unrewarding. He would tend to take refuge behind anecdotes and jokes. But when I tried to probe him about fundamental things – his religious beliefs, his feelings about women and children – I just got this echoing sound, that I was talking into a large, rather cool cave.

Nixon was a president riven with neuroses, a complex man who alienated the electorate and seemed to dissemble all too publicly. Reagan, by contrast, appeared the very epitome of assured self-confidence, a man of integrity with a convincing wholesomeness that made him absurdly popular amongst the sectors of the population who suffered most during his presidency (the lower middle-classes and ‘heartland’ poor). Yet the shared loneliness of both these presidents, their frustrated ambition and cool remoteness, make them much closer bedfellows than would first be assumed.

Edmund Morris offered up some wonderful insights into the difficulties of coming to know Reagan. He also provides the film with a poignant image of an Alzheimer-ravaged Reagan clutching a miniature model of The White House and saying that he doesn't know what it is, but he thinks it has something to do with him.

The closing interviews with former marine Andrew Bacevich – now an Academic and historian – are particularly fascinating and exemplary of Jarecki’s method. Bacevich is introduced to the viewer as a Reagan sympathiser, who voted for the president on both occasions during the 1980’s and was very much impressed by the positive message of ‘starting over’ that Reagan brought to American politics. However, Bacevich isn’t quite so sympathetic nowadays. Importantly, Bacevich highlights how history reveals the extent of a President’s legacy. During the 1980’s Reagan felt like the man for those times, offering stimulus to a failing economy by championing business interests and corporate America, renewing a sense of pride in American military prowess and taking the Cold War to the Soviet Union. Once Reagan leaves office however, there is a much clearer sense of where his ‘brand’ of American values leads the country. Bacevich strongly condemns the way in which Reagan’s platitudes and homilies allowed a valueless consumerism to seize the centre ground of American politics. More pointedly he demonstrates how the apparently clueless and ineffectual Carter, a President who seemingly lacked any policy direction, or overarching political narrative for his single term, actually had a far more astute sense of where America’s problems lay (with issues of energy and domestic policy). Jarecki’s film ultimately leaves you with a sense that despite his age and beliefs, Reagan was a thoroughly modern statesman, a politician who could play a part perfectly, convincing his audience of his humanity, integrity and the absolute validity of his ideology, whilst allowing that ideology to remain porous and fluid, meaning nothing and everything, to nobody and everyone.

Pros

- Jarecki manages to get a wide selection of interview subjects to contribute to the film.

- The period of the 1980’s is only just starting to come out from a certain historical obscurity that effects perceptions of recent events. This movie probably would not have been possible even five years ago.

- Jarecki’s understatement allows suggestions in the patterning of his narrative to gradually come to the fore.

Cons

- Reagan’s life, superficially, isn’t as intriguing as other great world leaders.

- There is little innovation within the movie, both in terms of form and content.

- Jarecki would appear to have a left-leaning bias in the documentary that will almost certainly enrage the extreme conservative right.

Rating:- 6.5/10